Passkeys are an easy and secure alternative to traditional passwords that can help prevent phishing attacks and make your online experience smoother and safer.

Unfortunately, Big Tech’s rollout of this technology prioritized using passkeys to lock people into their walled gardens over providing universal security for everyone (you have to use their platform, which often does not work across all platforms). And many password managers only support passkeys on specific platforms or provide them with paid plans, meaning you only get to reap passkeys’ security benefits if you can afford them.

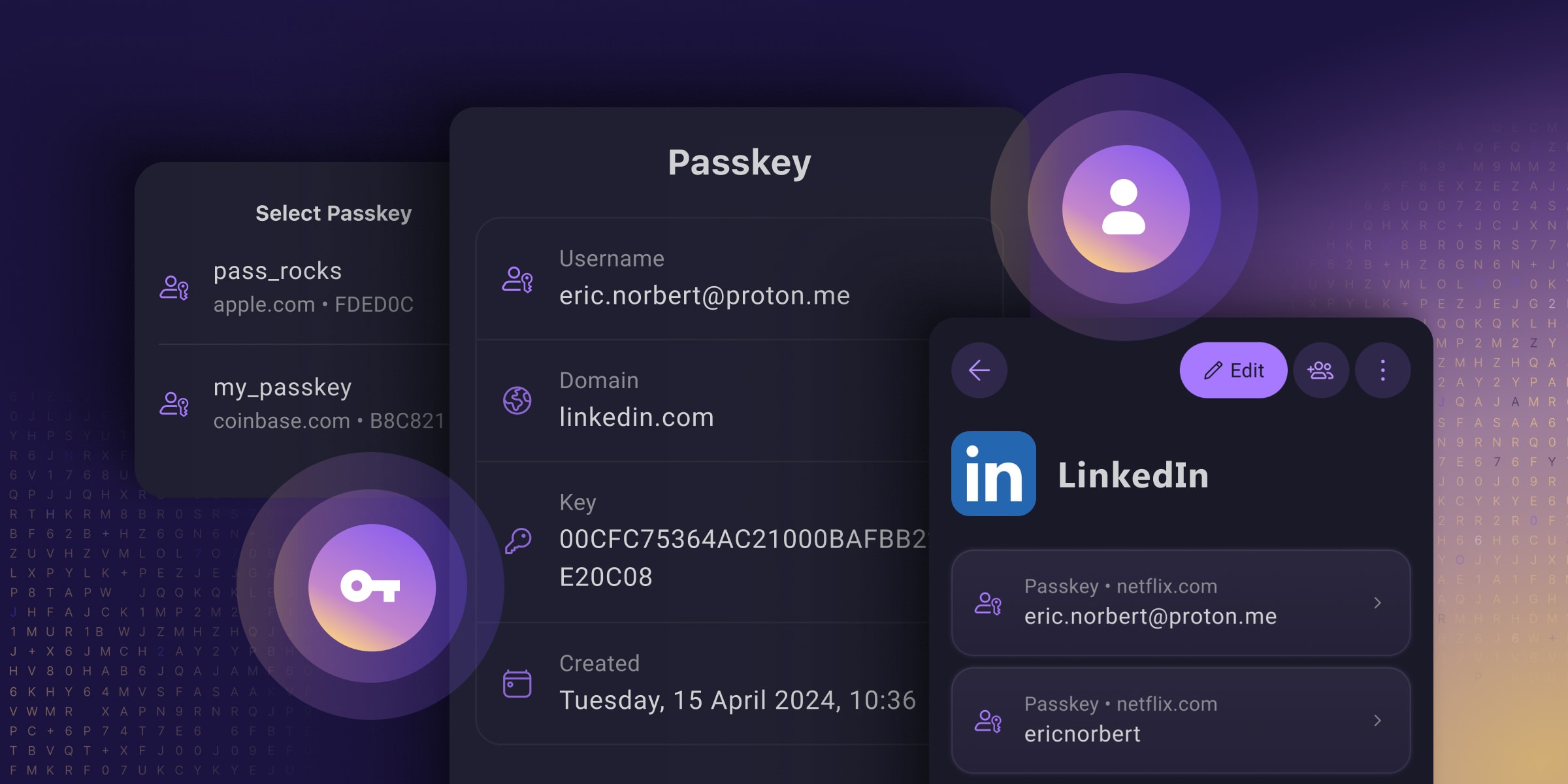

They’ve reimagined passkeys, helping them reach their full potential as free, universal, and open-source tech. They have made online privacy and security accessible to everyone, regardless of what device you use or your ability to pay.

I’m still a paying customer of Bitwarden as Proton Pass was up to now still not doing everything, but this may make me re-evaluate using Proton Pass as I’m also a paying customer of Proton Pass. It certainly looks like Proton Pass is advancing at quite a pace, and Proton has already built up a good reputation for private e-mail and an excellent VPN client.

Proton is also the ONLY passkey provider that I’ve seen allowing you to store, share, and export passkeys just like you can with passwords!

See https://proton.me/blog/proton-pass-passkeys

#technology #passkeys #security #ProtonPass #opensource

Could either you or @[email protected] explain this for me? If all that’s required to log in using a passkey is access to a single device/provider (e.g. Proton Pass in this case) how does it replace 2FA?

That’s because it’s not 2FA, strictly speaking. The second factor is whatever the device uses to verify you. So, essentially:

You go to a webpage, then go to sign up. Instead of inputting a password, you just input some ID, like a username or email. The device generates a cryptographic handshake with the webpage and your ID. You don’t (can’t, unless you can memorize a string of thousands of letters and numbers and be really good at math with prime numbers) have to remember it.

Now, when you go to login to that page again, the device just remembers and exchanges the keys with the webpage for you. That is NOT 2FA. But, you can configure your device to require another verification (most do). So, when you go to login, then the device asks you to use your fingerprint, or a remembered PIN. Or whatever that confirms that the one handling the device is indeed you before sharing encryption keys with the webpage. This is sorta 2FA, but not really because the webpage is delegating the second factor to the same device actually doing the login. Which might be compromised altogether, but that already happens with most 2FA implementations.

If you go to a second device, and wish to login, then your second device will fallback to other 2FA versions, like sending a OTP to the verified email or phone, or asking you to verify on the one device that is already logged in.

A passkey that’s generated on any given device is tied to that device, and is never sent to the server you’re authenticating to. What’s sent instead is a time based challenge/response that functions similarly to TOTP except that it’s not based on a shared secret like TOTP is. Since the Passkey is both a file, and is tied to the device you generated it on, it satisfied the something you have factor. Then in order to use a Passkey to authenticate, you need to unlock access to it using either biometrics (something you are) or a PIN (something you know).

Now storing your passkeys in a password manager does muddy the process of it a bit. The “something you have” part is no longer a device, but the key file itself, which is still arguably “something you have” but it is to a degree less secure than keeping it tied to a device. But you can think of storing passkeys in a password manager similarly to storing your TOTP in your password manager. It’s a tradeoff.

I know that with 1Password, even if I authenticate to my vault using my master password, when I go to use any particular passkey, it still requires biometrics.

Problem is that if the factor is not authenticated by the server, it doesn’t count. Not saying it’s not helpful, but it’s not part of the consideration when designing the security of the system.

The device can be attacked for an indefinite time and the server knows nothing about that. Or the device can disable that additional security either knowingly or maliciously and the server has no knowledge of that breach. So it’s still a single factor, “something you have” to the perspective of the server when considered security.

I’ve worked with healthcare data for decades and am currently a software architect, so while it’s not my specialty directly, it is something I’ve had to deal with a lot.